Mark McCartney and David Glass have produced a report on the decline of church attendance in Northern Ireland [i] which should, in my opinion, alarm and energise evangelicals. What follows is a brief description of their findings, but I urge you to read the more detailed, non-technical version here.

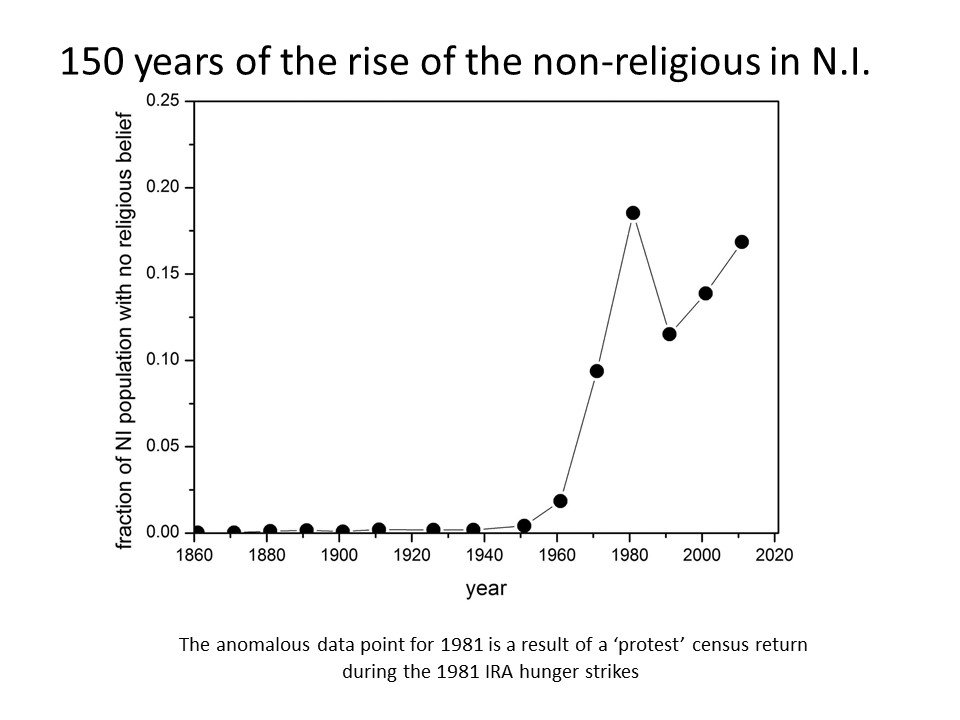

The decline in religious belief and corresponding rise in religious non-affiliation across the western world over the last century is well attested and widely discussed within academic literature[ii]. Unfortunately for us, Northern Ireland is no exception to this trend. Using Northern Irish census data, Mark and David have been examining the decline of the Christian denominations and the rise of the non-religious in Northern Ireland. Their final report makes for sobering reading, and should sound a wake-up call to Ulster’s evangelicals.

There has been a clear decline in the three main Protestant churches that begins in the era following World War II, the report focuses on the time period 1951-2011. Looking at the size of religious denominations as fractions of the NI population, some alarming figures leap out at the reader. For example, the size of the Presbyterian church, as a fraction of the population, has dropped by 36%. over the time period 1951 to 2011.

The decline in the main Protestant denominations is also replicated in almost all the smaller churches. At the 1951 census point the next five churches in order of size were, Brethren, Baptist, Congregational, Non-Subscribing Presbyterians and Reformed Presbyterians. With the exception of the Baptist church, all of these denominations are in clear decline, with decline being most pronounced in the Brethren church.

The Free Presbyterian church, though showing rapid growth in the 1950s-1980s, appears to have peaked at the 1991 census point. The Elim/Pentecostal churches are the one Protestant group that has shown clear sustained growth over the last 60 years. In 1951 it was the tenth largest Christian group in NI, whereas now it is seventh. There has also been a growth in those who simply identify as “Christian”. However, while the Elim/Pentecostal churches and those identifying as simple “Christians” are growing, it must be noted that these two groups make up a very small fraction (about 1.5%) of the population; their growth is more than negated by the decline in the other religious groups.

It is also unclear from the data whether such growth is, in the case of the Elim/Pentecostal churches, conversion growth, or growth via individuals joining by transferring from other denominations. Similarly in the case of the increasing number identifying as ‘Christian’, this could be for a number of reasons- a growth of independent churches (again via either conversion or moving from other denominations), or a conscious decision to give primacy to the term ‘Christian’ rather than a denominational label. It is disappointing and disturbing that a rapidly increasing number of people are either not returning a religious affiliation, or explicitly stating that they do not have one.

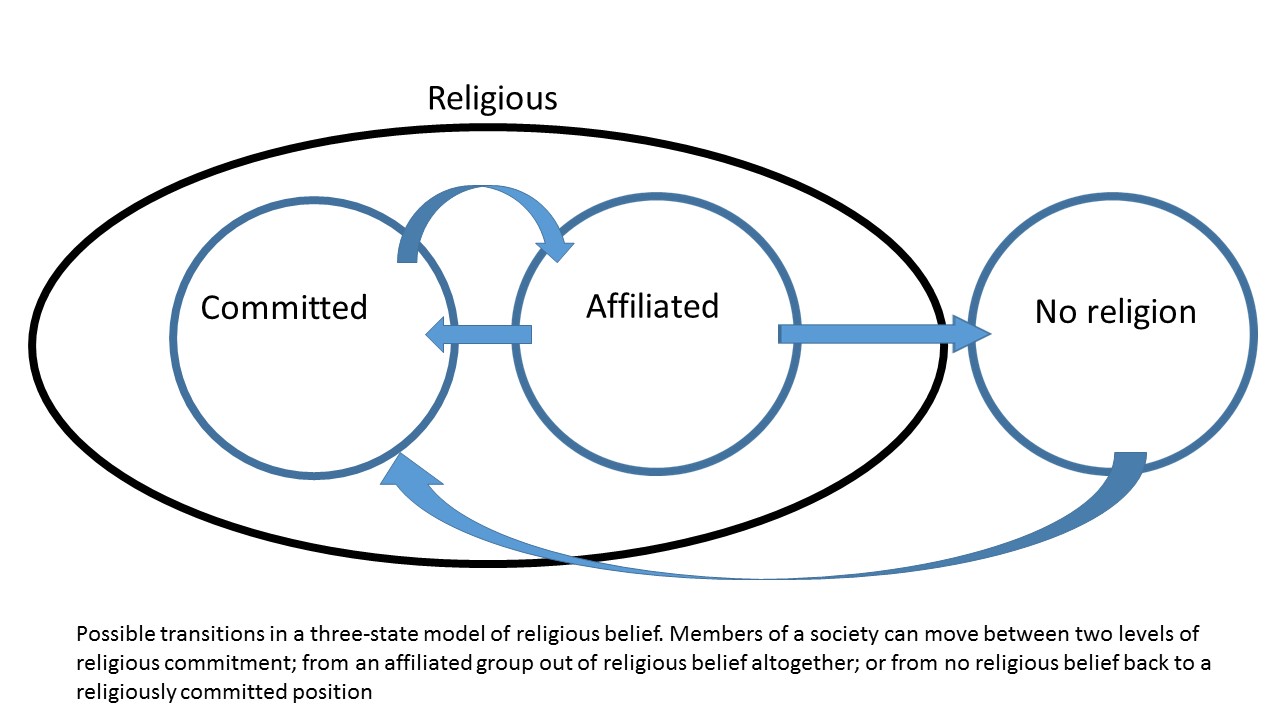

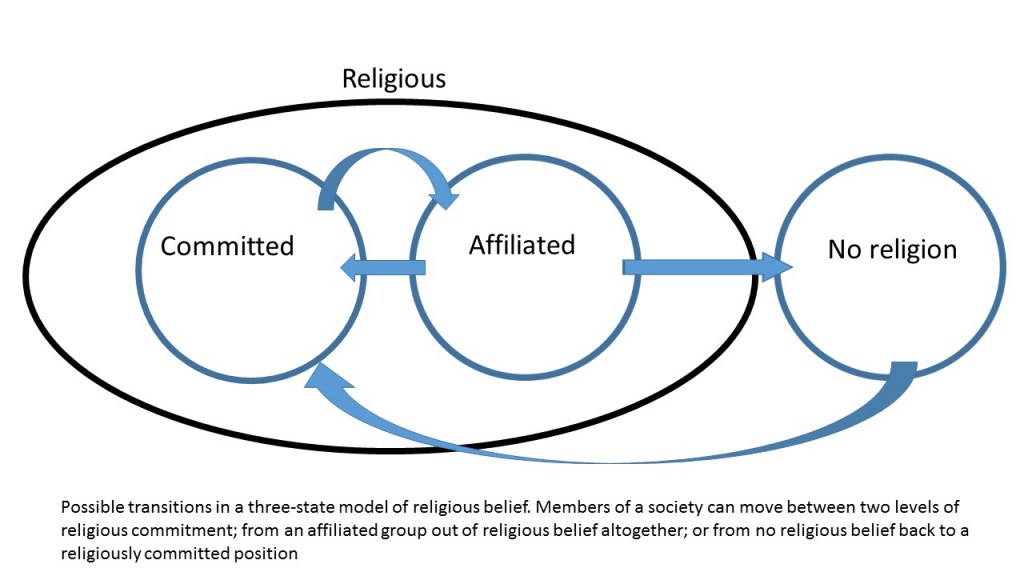

Some academic work[ii] in this field has sought to model the change in religious affiliation via a ‘two-state’ model – with members of the society being either ‘religious’ or ‘not-religious’. The report uses a stronger modelling strategy as there is more than one level of religious commitment within any given religious group. To attempt to account for this David and Mark constructed a model where society is partitioned into three groups:

1. The religiously committed 2. The religiously affiliated 3. The non-religious[iii].

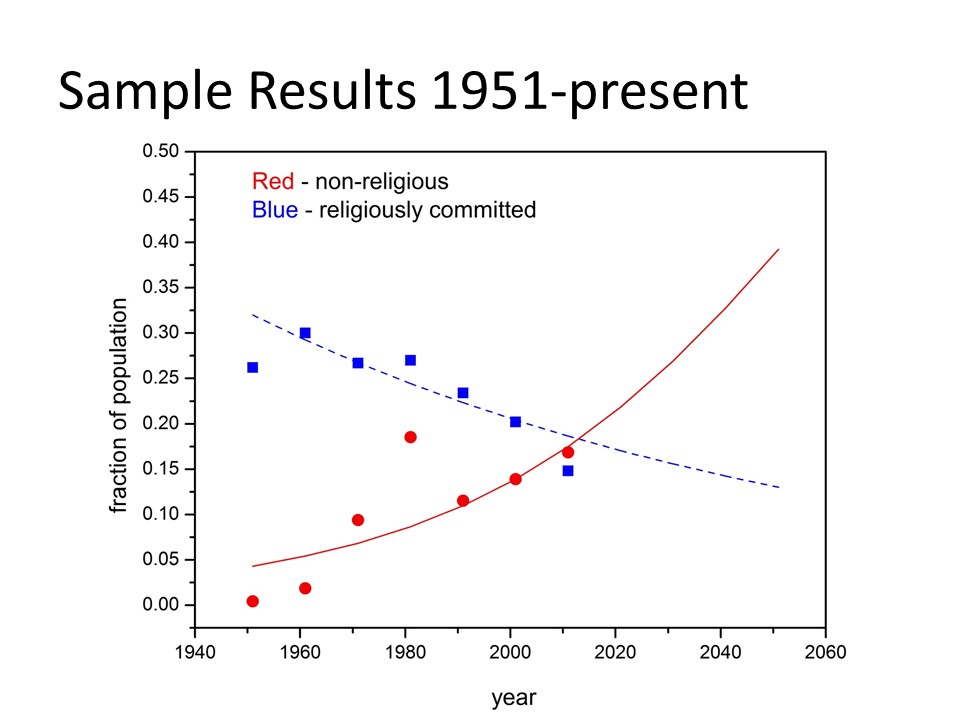

Without going into details, six separate mathematical models were constructed to represent movements between the three groups, using two different estimates for the level of religious commitment in Northern Ireland. This resulted in a total of twelve sets of scenarios for the changes in religious belief in Northern Ireland over the time period 1951-2011, with associated predictions for how belief levels would change in the future.

These model scenarios predict that the non-religious section of NI society will continue to rise reaching between 19% and 22.1% of the population by the 2021 census point and between 24.0% and 33.8% by 2041 (with the wide range of the prediction for 2041 being inevitable as we project further into the future). Secondly, the models all predict that the size of the religiously committed group will continue to decline. Finally the twelve scenarios all suggest that reconversion rates from the non-religious group are negligible, being at most 0.05% or 1 in 2000 of the non-religious population being converted per year.

The NI census provides stark and robust data on the decline in religious identification across a wide range of denominations. A possible response is that while the merely affiliated are drifting away from the church, the committed core remains. However, the data shows that the communicant core of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland is also declining, and it is reasonable to assume that this is also the case for other denominations[iv].

Part of the reason for this may well be a failure to, if you will forgive the phrase, ‘efficiently’ pass the Christian faith onto the next generation within the church, and this has been argued by other authors. The most important implication of the mathematical models described in outline in this report is that they suggest that the strategies used by Christians in NI to reach out to people who have no religious belief are having negligible impact.

Of course, we are not arguing that the movement of the Holy Spirit can be mathematically modelled. No one is attempting to. The models only describe levels of commitment to particular denominations, not what is going on in people’s hearts. But the models do give us some indication of how seriously people take Christianity; they also indicate that our evangelism is not drawing people back to churches on a regular basis. Faith in the Holy Spirit is not an excuse to ignore patently obvious facts, or for deliberately pursuing strategies which have proven to be practically useless.

While the report makes for uncomfortable reading, and may even be unwelcome news to some, the implication is that churches in Northern Ireland need to think carefully about their evangelism. There is strong evidence that the Christian message is not being effectively preached to the rising number of people who declare themselves of ‘no religion’.

[i] Their report was made possible by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation (Grant no. 40676). The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation.

[ii] An overview of aspects of the decline of religion can be found in Steve Bruce, Religion in the Modern World, OUP, (2000), pp. 29-37.

[iii] For relevant work, see references in M McCartney and DH Glass, A three-state dynamical model for religious affiliation, Physica A, 419, (2015) 145-152.

[iv] Non-religious should not be read as “agnostic”, “atheist” or “secular humanist”. The non-religious are a diverse group: in 2011 in Northern Ireland the non-religious were comprised of 179,951 people of ‘no religion’, 122,252 who did not state a religion,1462 ‘Jedi Knights’, 1011 ‘atheists’, 478 ‘agnostics’, 179 ‘humanists’, 59 ‘heavy metals’, 17 ‘free thinkers’, and 7 ‘other’.

[iv] For example, the communicant rolls of the Reformed Presbyterian Church are also falling