There are some subjects which can only be approached with fear and trembling – and this is certainly how I feel about the topic of assisted dying. Make no mistake – I believe that every human being is made in the image of God; I also believe that it is wrong to deliberately kill any innocent human being. However, I am sure that I would feel a great temptation to take an innocent life if someone I loved deeply was dying and in great pain. I am in no rush to judge the motivations of those who support assisted dying because I too will be judged; and the measure I use to judge others might be used to measure me.

However, though I beg patience from those who will disagree, I do not believe that killing is an adequate response to human suffering. Generally, euthanasia campaigners muddy the waters by adding “safeguards” to proposed legislation. The tendency is to appeal for a right to “assisted dying” rather than argue for euthanasia. But there is no substantial difference between euthanasia and assisted dying; and the proposed safeguards do not seem at all safe.

In Britain, under the terms of proposed Assisted Dying Bill, very soon a person could be lawfully be provided with assistance to end his own life if he is both terminally ill and requests aid. He must be 18 or over, be diagnosed by a registered medical practitioner as having an inevitably progressive condition which cannot be reversed by treatment and have a clear and settled intention to end his own life. He must also sign a declaration declaring their intent to take their own life in front of two medical practitioners.

This legislation is much more dangerous than it sounds. First, Physician Assisted Suicide has a small, but very real, failure rate. For example, a patient might vomit up medication or begin to choke. In these instances a doctor will intervene to end the patient’s life. So the right to die inevitably and swiftly translates into a doctor’s legal right to kill.

This legislation is much more dangerous than it sounds. First, Physician Assisted Suicide has a small, but very real, failure rate. For example, a patient might vomit up medication or begin to choke. In these instances a doctor will intervene to end the patient’s life. So the right to die inevitably and swiftly translates into a doctor’s legal right to kill.

Second, British law would recognise that under certain circumstances suicide can be a rational choice. And not only would suicide be considered rational under certain conditions – others would have an obligation their medical expertise to help people kill themselves. So by passing this Bill, Parliament will send a message that to the lonely, the bereaved, the broken, the anguished and the frightened that suicide is reasonable. It is worth noting that two years after physician assisted suicide was introduced in Oregon the suicide rate among those aged 35-64 increased by almost 50%.

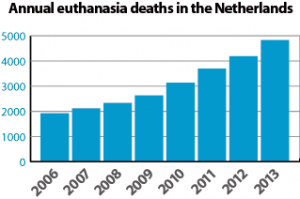

Worse, whichever logic underlies the bill, an incremental extension of the categories of people qualifying for euthanasia will inevitably follow. There can only be two grounds for euthanasia. We may judge that some lives are no longer worth living; or we might argue that every human being should have a right to choose the manner of their own death.

Suppose the bill is justified by an appeal to the individual’s “right to choose”; then it seems entirely arbitrary and irrational to restrict assistance to those who have only six months to live. Then suppose I decide that my life has no dignity or meaning because suffer from depression or chronic arthritis. If the state really respects my right to choose how and when I die then it will allow others to assist me. But this seems absurd. Hopefully society will continue to punish those who encourage and enable others to commit suicide.

So advocates for the bill attempt to justify it by a perceived need to relieve suffering. That is, they argue that some forms of euthanasia are justified because some lives are no longer worth living. Of course, because suffering is private it is best for experts to seek the patient’s thoughts. If he or she believes his or her life is unbearable, then doctors have excellent evidence that this is a life that has become too burdensome. Furthermore, no medical procedure can be carried out on a person without their permission – so informed consent will remain important.

But once more, there seems to be no rational warrant for the safeguards built into Lord Falconer’s bill. It seems entirely arbitrary to restrict euthanasia for those who have only six months to live. There are many more ways to suffer. Moreover, if some lives are so burdensome they are best ended then it is obviously unfair to limit euthanasia to those who can ask for it. Why should infants, children, or the mentally incapacitated be burdened with unnecessary suffering? If the aim of the bill is to relieve suffering, human autonomy seems neither here nor there. Some form of non-voluntary euthanasia will must follow.

But once more, there seems to be no rational warrant for the safeguards built into Lord Falconer’s bill. It seems entirely arbitrary to restrict euthanasia for those who have only six months to live. There are many more ways to suffer. Moreover, if some lives are so burdensome they are best ended then it is obviously unfair to limit euthanasia to those who can ask for it. Why should infants, children, or the mentally incapacitated be burdened with unnecessary suffering? If the aim of the bill is to relieve suffering, human autonomy seems neither here nor there. Some form of non-voluntary euthanasia will must follow.

Worryingly, the power of life or death ultimately ends up in the hands of medical and legal experts. If doctors are sure that a child is terminally ill and enduring suffering, why shouldn’t they have the right to overrule parents who are too emotionally invested to make rational decision? “Not Dead Yet”, a network of disabled people in the UK who oppose euthanasia warns that

The distinction between disability and terminal illness is a myth. Definitions of ‘terminal illness’ can never be precise. For example people with Multiple Sclerosis are disabled people and yet they are the people targeted most frequently as beneficiaries of assisted suicide legislation. This serves only to create a false distinction between those who will be legally able to request assisted suicide and others who will not. In this way, proponents claim they seek a small change in the law. But this is a crack that can be steadily opened wider and wider until any person may assist another disabled person to die without consequence.

Charities who advocate for the disabled are worried about the long term effect on the public’s attitude to the ill and the disabled – and also how those who ill or disabled might come to view themselves. For example, Scope worries that

The campaign to legalise assisted suicide reinforces deep-seated beliefs that the lives of disabled people are not worth as much as other people’s. It’s a view that is all too common. The current law against assisted suicide works. It sends a powerful message countering the view that if you’re disabled it’s not worth being alive, and that you’re a burden.”

Finally, we should note that medical interventions which relieve suffering will not count as “treatment” under the terms of the bill. Even if palliative care could achieve complete and total pain relief doctors would still be allowed to kill their patients. This makes palliative care redundant. The cheapest, most effective cure is to kill the patient and we live in a time when governments and health-care providers are tightening their belts.

Of course, doctors should be under no obligation to preserve life when treatment becomes burdensome and futile. Furthermore, it can be perfectly acceptable to risk shortening a life to administer palliative care. After all, palliative care targets suffering – it does not exist to take a life away. But if society recognises suicide as rational, and if it grants medical experts the authority to kill, then it might not be long before the terminally ill are made to feel a moral obligation to die quickly and quietly. And in that case, Britain will not be a safe place to be very ill or aged.