For a long time, Christian apologists have not had to worry too much about politics. Not so long ago Marxists of various persuasions argued that Christianity sedated the poor and the powerless; only the rich and the powerful truly benefited from a message of forgiveness, love and the hope of heaven. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, however, orthodox secularists either accept the merits of the free-market or some form of social democracy and Christianity seems quite compatible with both. Indeed, and quite amusingly, there are evangelical Christians who think that the Bible teaches the Scandinavian model and just as many with proof texts for true “red, white and blue” free-market capitalism.

Political arguments against orthodox Christian belief have not disappeared, however. To avoid offending their benefactors many politicians on the left have sometimes been reluctant to challenge “big business”. A cheaper way of establishing their left-wing credentials has been to attack conservative religious beliefs about sexual morality and the sanctity of life. It seems that politician or journalist can promote cuts to unemployment benefits yet still promote his compassionate nature by supporting gay marriage or Planned Parenthood. Christians are often too slow to point out that politicians just might be attacking their beliefs for political reasons.

Political arguments against orthodox Christian belief have not disappeared, however. To avoid offending their benefactors many politicians on the left have sometimes been reluctant to challenge “big business”. A cheaper way of establishing their left-wing credentials has been to attack conservative religious beliefs about sexual morality and the sanctity of life. It seems that politician or journalist can promote cuts to unemployment benefits yet still promote his compassionate nature by supporting gay marriage or Planned Parenthood. Christians are often too slow to point out that politicians just might be attacking their beliefs for political reasons.

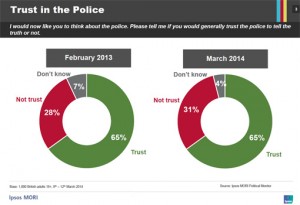

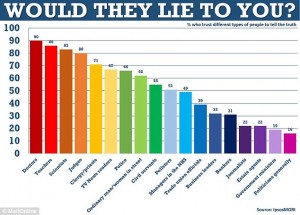

So apologists should pay a more attention to politics. This need is all the more pressing because politics is giving faith a very bad name. The current crisis of faith goes far beyond an incredulity towards meta-narratives or a hostility to Christian doctrine. Simply put, poll after poll reveals that we no longer trust anyone with authority – and with good reason.

In Britain, while few ever believed there was a lot of honesty in the financial sector, numerous crises led us to doubt that the City was even competent. Scandals over Parliamentary expenses banished any hope that MPs could regulate their own behaviour. Faith in the press vaporised when journalists for leading tabloids engaged in criminal activity, including phone-hacking and police bribery. When it materialised that their editors had significant influence with senior politicians, trust in Parliament eroded even further. The BBC, the ‘gold standard’ of British broadcasting, was excoriated for shelving reports which revealed that one of its oldest stars, Jimmy Savile, was a serial sex abuser.

Britain had grown used to stories about clerical abuse; celebrity abuse was relatively new. But faith in “the system” evaporated when news emerged that police and social workers in Yorkshire, Oxfordshire and Greater Manchester had simply ignored the abuse of teenage girls at the hands of paedophile gangs for years. It seems that we cannot trust the watchmen or those watching over them. And family breakdown means we can no longer even take our parents on their word. Trust is out of fashion and cynicism is in vogue.

For Christians, faith simply means a deep personal trust in God; and trust can seem a little naive when we have been failed by those in authority so many times. However, we are not called to have faith in the Church or churchmen, but in Christ. This trust is not blind – indeed, faith is rational because it is illuminating: it makes sense of the world and our lives. Christianity even makes sense of the mess that our society is in and points us in a better direction.

For Christians, faith simply means a deep personal trust in God; and trust can seem a little naive when we have been failed by those in authority so many times. However, we are not called to have faith in the Church or churchmen, but in Christ. This trust is not blind – indeed, faith is rational because it is illuminating: it makes sense of the world and our lives. Christianity even makes sense of the mess that our society is in and points us in a better direction.

In the Christian world-view we are all damaged goods; we are in God’s image but we have gone astray. No human institution or practice is free from the corrupting power of sin. So anyone should prepare for a fall if he believes that the market can deliver us by its invisible hand. Social programmes will not bring peace and justice either; they make too many dependent on the patience of too few. Rational self-interest and enlightened altruism seem so promising – but humans can be absurdly irrational, cruel, proud and self-destructive. It is little wonder cynicism reigns when we put our trust in human schemes. However, the Christian does not counsel despair. There is more to us than our sin; we remain in God’s image even if we have marred it somewhat.

But can Christians do anything about the mess we’re in? We need Christian political action beyond the polling booth. Consider: in Britain, the NSPCC has estimated that 1 in 9 children are neglected or abused. The vast majority of cases are not reported – and if they were, the national economy would collapse trying to meet their needs. Children cannot survive without a community which cares for them. If it takes a village to raise a child, the Church can provide the village. Families can be supported and guided; children can be watched over by a community which sees their needs.

Now, Christians should speak prophetically on the sanctity of life, covenantal marriage and religious tolerance. But Christian political witness begins by helping whoever we can, however we can, while we still can. This challenges what the powerful can achieve and demonstrates the limits of governments and markets. For ultimately every programme, initiative and strategy will fail without compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience, all bound together in love; and this can only be achieved in God’s kingdom.

Of course, as the examples of Shaftesbury and Wilberforce show, corruption need not stop good politicians bringing about great political goods. But Christians should not hitch their wagon to a particular political party. “Liberty of conscience” is an important Christian doctrine: individual Christians have the right to form their own opinions about a wide variety of policies and programmes.The Bible is clear that we should respect creation – but it does not tell us how to interpret the data about global warming. The Bible tells us to protect the poor, respect property and obey the government – but it does not make suggestions for ideal tax-free personal allowances.

Furthermore, we must not give the impression that Christianity is primarily about moralism, social conservatism or even the redistribution of wealth. We need to be clear: Christians do not evangelise so that citizens will vote in a socially conservative manner; we do not preach so that people will assent to the Christian world-view. The Sadducees were social conservatives and the devil’s metaphysics are probably quite sound. Instead, we preach faith in Christ and a labour that comes from love. Only a hope stored up in heaven insures against cynicism now on Earth.