There is no good reason to think that there is a necessary conflict between science and the existence of God; but is there still some way in which science might support atheism? One approach is to say that while science does not disprove God’s existence, it can still undermine it via ‘explaining away’.

Over the past few hundred years, the progress of science has worked to strip away God’s roles in the world. He isn’t needed to keep things moving, or to develop the complexity of living creatures, or to account for the existence of the universe … Two thousand years ago, it was perfectly reasonable to invoke God as an explanation for natural phenomena; now, we can do much better.” Sean Carroll, ‘Does the Universe need God?’

This strategy appeals to “Ockham’s razor”, the principle that there is no need for two explanations (God and science) to account for the world around us when one (science) will do. Ockham’s razor can be a very useful tool, but in the wrong hands it can also be very dangerous. The challenge is to determine how to use it appropriately. Sometimes it is quite right to adopt only one of two explanations, but in other cases it is entirely reasonable to accept both explanations.

This strategy appeals to “Ockham’s razor”, the principle that there is no need for two explanations (God and science) to account for the world around us when one (science) will do. Ockham’s razor can be a very useful tool, but in the wrong hands it can also be very dangerous. The challenge is to determine how to use it appropriately. Sometimes it is quite right to adopt only one of two explanations, but in other cases it is entirely reasonable to accept both explanations.

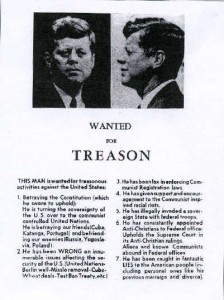

Consider the assassination of JFK in 1963. If a “lone gunman” hypothesis could be verified, there would be very little need to invoke a “conspiracy hypothesis”. If there was no clear compelling evidence linking JFK’s killer to a band of conspirators, then the conspiracy hypothesis has been explained away. Given the eyewitness and forensic testimony there no need to hypothesise numerous shooters. And in any case, most conspiracy theories hypothesise numerous agents with fiendishly complicated plans. The conspirator’s reasoning is often unclear: why would the CIA, or the FBI, risk the a complicated and elaborate scheme to kill the president when they simply could have leaked information about JFK’s lurid affairs just before the next Presidential election?

But does a “lone gunman” hypothesis give us a deep, satisfying explanation for the assassination of President Kennedy? Frankly, that’s doubtful. One reason conspiracy theories thrive is the “Lone Gunman” hypothesis relies on so much luck. What are the odds that the one man who wanted to kill the President would just happen to have the right training, the right equipment, and be working in the right building on the right day for a perfect shot? There was significant domestic social upheaval, and considerable international tension, during JFK’s first term. Yet no effort was taken to improve the President’s safety. A ‘perfect storm’ was brewing. As is natural in a time of political and social upheaval the President had frustrated and angered sections of the American public. In the early 1960s, many individuals would have wished the President harm; lax security made it likely that one of them would succeed.

The “Lone Gunman” hypothesis explains away the “Conspiracy” because the two compete and a lone gunman better accounts for the evidence. But the “Perfect storm” hypothesis in no way competes with the “Lone Gunman” hypothesis; indeed the former makes sense of the latter. So many people wanted to harm the President in the early 1960’s, and so little effort was made to protect the President, it simply isn’t surprising that one madman made it through security to achieve his goal. ”

So, does science explain Christianity away? Well, the two hypotheses are hardly incompatible. It is true that scientists have discovered laws of nature, and physical processes, which explain many of our observations. But, as Kepler, Galileo and Bacon would have told us, these discoveries do not explain God away. The first scientists were motivated to search for laws and mechanisms in nature precisely because they believed the universe was designed by a rational agent; they expected to find an ordered rational structure in nature because they were theists!

So, does science explain Christianity away? Well, the two hypotheses are hardly incompatible. It is true that scientists have discovered laws of nature, and physical processes, which explain many of our observations. But, as Kepler, Galileo and Bacon would have told us, these discoveries do not explain God away. The first scientists were motivated to search for laws and mechanisms in nature precisely because they believed the universe was designed by a rational agent; they expected to find an ordered rational structure in nature because they were theists!

Theism and science are compatible because theism encourages us to seek laws and mechanisms. So science and atheism, as a matter of logical and historical fact, do not imply one another. Indeed, the hypothesis of atheism does not make it at all likely that we would live in a universe governed by rationally comprehensible laws. Christians believe that the universe has a rational creator, and that we are his rational creations. If there is a God, it is not at all surprising that the universe has a rational, comprehensible structure.

So the success of science is not only compatible with Christian theism; theism is confirmed by scientific discovery. Why is our universe beautiful, intricately structured and delicately ordered? Why is our universe governed by laws and mechanisms? Why can those laws be expressed in the language of mathematics? These are not scientific questions which can be answered by precise measurements and mathematical models. And if theism and science do not attempt to answer the same questions, they do not compete with one another.

Such questions must be answered by world-views, like atheism and theism. Atheism must answer that we simply got lucky – we just happen to live in a universe with a rational structure and comprehensible laws. But, as the case of Lee Harvey Oswald illustrates, we do not accept “luck” as an an explanation if there are other, better explanations on offer. So theism answers that we are not the beneficiaries of incredible luck; the universe was created, and is ordered, by a rational agent—God. So Christianity achieves what atheism cannot: Christian theism illuminates and adds depth to the discoveries of science.