There’s no conflict between evidence and Christian faith, but they aren’t the same thing either. Christian faith involves trusting God and while that can be based on reason and evidence – for the existence and trustworthiness of God – it goes beyond it too. With regards to trust, the same thing occurs when trusting other humans. We might weigh up the evidence about a person’s trustworthiness, but actually trusting them is another matter – it requires going beyond the rational assessment of evidence to doing something about it.

Often on this site we’ve looked at objections to Christian belief raised by people who are highly sceptical, but many people aren’t so sceptical at all. Some people might think the case for belief in God and / or the central claims of Christianity is somewhat plausible, but overall they are still moderately sceptical. Others might think the case is reasonably good, but they are not completely convinced. What should such people do? How much evidence do they need in order to believe? Do they need to be completely certain? Or would it suffice to have just enough evidence to make belief more plausible than not? Or is framing it in terms of the amount of evidence needed the wrong way to think about it?

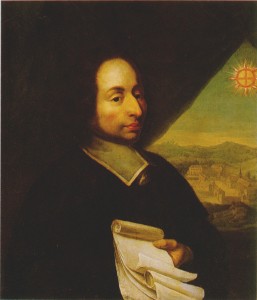

Blaise Pascal and William James had a lot to say about this. Pascal’s wager is very well known. He argued that in cases where reason cannot decide, the consequences of different courses of action should to be taken into account. Basically, he claimed that you’ve everything to gain and nothing to lose, so you should wager for God.

Blaise Pascal and William James had a lot to say about this. Pascal’s wager is very well known. He argued that in cases where reason cannot decide, the consequences of different courses of action should to be taken into account. Basically, he claimed that you’ve everything to gain and nothing to lose, so you should wager for God.

James similarly argued that in certain cases we must decide between two beliefs. The two beliefs must be live options – that is, both must be realistic possibilities; the option must be forced in the sense that a choice between the two beliefs is unavoidable; and it must be momentous in the sense that a unique opportunity rests on the choice. In such a scenario, James argues that we can and must make a choice.

My goal here is not to defend either Pascal’s or James’ arguments, but I do think they were right to emphasize that the significance of the beliefs in question should be taken into account. I also think that when it comes to belief in God they were right that there is a forced option or as Pascal put it “There is no choice, you are already committed.” Of course, in another sense, one could remain agnostic, but if there is a God who is the source of all goodness and every perfection and who has created us so that we might know him, then we miss out on this – indeed on the very purpose for our lives – by remaining agnostic.

Still, it’s not at all clear you can just decide to believe, so what do you do? Let’s return to the evidence question. It’s important to remember that we don’t need to have certainty before holding a belief. If we did that, we’d hold virtually no beliefs at all. After all, we could be mistaken about loads of things, but that doesn’t mean we become sceptics about all of them. Also, there can be more to finding the truth than just weighing up the evidence in a neutral, detached manner. Perhaps that’s suitable in some contexts, but let’s think again about trusting another person. Suppose you try to evaluate the person’s trustworthiness and are unsure. One option is, of course, to do nothing, but you could miss out on the value of the person’s friendship. So another option is to take some steps to get to know the person better; perhaps as you do so you’ll be better placed to evaluate their trustworthiness.

Arguably something similar goes for belief in God. Here there is a danger in missing out on something much greater – the knowledge of God – so doing nothing doesn’t seem very prudent, but what steps can you take? One step is to investigate the evidence further. Another is to investigate it from a personal or experiential point of view. Just as in the case of another human, it doesn’t make much sense that we could come to know God by simply evaluating evidence in a neutral, detached manner (although that might be a good place to start). As the philosopher Paul Moser has pointed out, a God worthy of worship would not be interested in our simply acquiring abstract knowledge about him, but would want to transform our characters.

But how do we investigate Christianity personally and experientially. Pascal suggested getting involved. There is no reason why someone who is still undecided cannot pray, asking God if he is there to make himself known to them, and the same applies to reading the Bible and getting involved with other Christians, perhaps by attending a Church or some other sort of group or course. None of this means that critical faculties must be set aside, but it does illustrate a desire to seek after the truth – and perhaps in doing so you’ll find it.