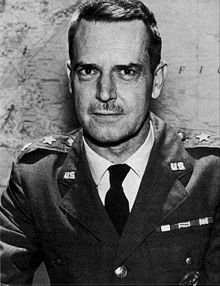

After the Second World War, many of the Filipino partisans who had fought the Japanese turned their guns on corrupt landlords. Fearing a communist takeover, the CIA sent Colonel Edward Landsdale to save the region from the Red Peril. Landsdale had two outstanding qualifications: he had prior experience of liaising with the Philippine guerrilla forces and he was a former San Francisco advertising executive. He knew that the Huk rebellion could not be prevented through force of arms alone. Rather, it required psychological and political warfare.

After the Second World War, many of the Filipino partisans who had fought the Japanese turned their guns on corrupt landlords. Fearing a communist takeover, the CIA sent Colonel Edward Landsdale to save the region from the Red Peril. Landsdale had two outstanding qualifications: he had prior experience of liaising with the Philippine guerrilla forces and he was a former San Francisco advertising executive. He knew that the Huk rebellion could not be prevented through force of arms alone. Rather, it required psychological and political warfare.

As well as winning over the hearts and minds of peasants and patricians to the American war, Landsdale used the ‘black arts’ of psychological warfare. One of his favourite psy-op techniques was to send soldiers into villages at night to paint “evil-eye” icons on the walls of houses facing the homes of suspected terrorists. Suspects were terrified by that they had been cursed; morale amongst the “Huk” rebels plummeted.

Bizarrely – yet effectively – Landsdale enlisted vampires and soothsayers in his cause. His agents spread a rumour that a famous clairvoyant called Ilocos Norte had prophesied that the asuang , a local vampire, would prey on the dark hearted. Commandos then seized a lone Huk sentry and strangled him. The body was exsanguinated, hung upside-down from a tree, and two puncture holes were made in the jugular. Huk guerrilla units lived on the edge of their nerves in swamps and on mountains; the constant threat of betrayal or ambush made paranoia an essential life skill. So when the unfortunate sentry’s comrades discovered him the next morning they believed that the undead had taken sides with Uncle Sam and fled to a safer region.

In the worst years of Northern Ireland’s troubles, British military intelligence attempted a similar operation. They wanted Christians to believe that paramilitary violence had opened a door to dark forces. Agents leaked stories to newspapers about black masses, placed black candles in abandoned buildings, and rumoured that some murders were “ritual killings”. The operation was not successful. This campaign failed to slow the growth of paramilitarism; Ulstermen didn’t believe that the devil’s followers had rode out in the towns of Tyrone, Armagh and Down.

It would be nice to believe that the American operation succeeded and the British operation failed because Ulster’s evangelicals were a community of rational, critical believers. I’m not convinced. The Americans targeted specific individuals – suspected terrorists – with a specific aim – to shock and demoralise them. Whereas British Intelligence simply wanted to create a subtle link in the public’s minds between terrorism and supernatural evil. Someone should have told them that subtlety isn’t our defining characteristic. No-one linked Satanism with terrorism; but many gleefully accepted that supernatural forces were at work in our province.

It would be nice to believe that the American operation succeeded and the British operation failed because Ulster’s evangelicals were a community of rational, critical believers. I’m not convinced. The Americans targeted specific individuals – suspected terrorists – with a specific aim – to shock and demoralise them. Whereas British Intelligence simply wanted to create a subtle link in the public’s minds between terrorism and supernatural evil. Someone should have told them that subtlety isn’t our defining characteristic. No-one linked Satanism with terrorism; but many gleefully accepted that supernatural forces were at work in our province.

Just about every town in Northern Ireland has an urban legend about an obscure local field where devil worshippers used to gather to sacrifice goats and chickens. In the late 1970s and 1980s Ulster’s fundamentalists panicked about Satanists recording their subtle plans backwards on music tracks. We worried that the anti-Christ was about to seize control of the European Union. True, there is an international market for tall tales about occultists and covens. But those tales found fertile soil in Ulster. The efforts of black-operations encouraged evangelicals to fear black magicians.

It is depressing to read that the head of the British army’s “black operations” unit viewed Northern Irish evangelicals as “very superstitious”; he knew that if he updated a few ghost stories many of us would buy them. Perhaps we were not so superstitious, however, as we were credulous; willing and able to accept any story that confirmed our worldview. I wish the problem was confined to Northern Ireland. However, we are plagued with the problem of what journalist Janet Mefferd has called “low-information Christians”: believers who have strong beliefs, but who haven’t thought about why they believe any of them. They just accept whatever they hear, if they hear it from the right sort of preacher; then thy act on whatever they’ve heard without worrying about the consequences.

It is depressing to read that the head of the British army’s “black operations” unit viewed Northern Irish evangelicals as “very superstitious”; he knew that if he updated a few ghost stories many of us would buy them. Perhaps we were not so superstitious, however, as we were credulous; willing and able to accept any story that confirmed our worldview. I wish the problem was confined to Northern Ireland. However, we are plagued with the problem of what journalist Janet Mefferd has called “low-information Christians”: believers who have strong beliefs, but who haven’t thought about why they believe any of them. They just accept whatever they hear, if they hear it from the right sort of preacher; then thy act on whatever they’ve heard without worrying about the consequences.

The result, of course, is to bring the Gospel into disrepute. The apostles were proud of the fact that they would not be taken in by “cunningly devised fables”. They repeatedly referred to eyewitness testimony which could be publicly challenged and verified. The epistles insist that churches beware of “deceivers” claiming miraculous insights. To be open to the possibility of the miraculous does not mean that we should accept every miracle claim with slack-jawed credulity.

Christians should expect miracles to be rare and to be events that God has good reason to bring about. Obviously, miracles lose their significance if they are not exceptional events. So we would not expect every miracle report to be true. The Christian world-view insists that we should not uncritically accept every miracle claim at face value. Faith is not an excuse for stupidity; in fact faith – fearing, and therefore depending upon, the Lord – should be the beginning of wisdom. We ought to be more discerning than our secular neighbours, not less!

Take a preacher who claims to have miraculous visions. He forces a trilemma on us: he is either delusional or lying, or he is telling the truth. If his claim is false, he is either committing a very serious sin or is in very poor mental health. If his claim is true, we all ought to take all of his claims more seriously! A Christian leader has a great deal to gain by claiming that he has had a sensational vision. He has nothing to lose from making claims which cannot be falsified and that are unlikely to be challenged.

Suppose that preacher claims to be able to specific church members committing specific sinful acts; he would gain a tremendous amount of personal authority. An accusation from such a seer would carry tremendous weight. Even if no corroborating evidence was found, the accused could remain under suspicion for quite some time. He would be claiming an authority that puts him on a par with the Old Testament prophets. Scripture (and common sense) teaches us that any claim to such miraculous insight must be rigorously tested.

If there is evidence of dishonesty and manipulation elsewhere in a visionaries’ ministry we should be highly dubious of his claims to see our secret sins. If the prophet describes his vision in lascivious detail, we have reason to be sceptical. We are commanded not to judge others by standards we cannot meet ourselves; this is not a call to naivety and intellectual cowardice. A secularist might be intrigued by the possibility of paranormal events. The Christian believes that the work of God and the health of God’s people is at stake when someone stakes a claim to a miracle. So we should test such claims rigorously precisely because we believe God can work wonders; we do not want his name brought into disrepute.

We should not be willing to believe any story provided it is sensational enough. Like the apostles, we should demand strong testimony and evidence that an exceptional event has occurred; we should know that God would have good reason to give us this sign; above all, this sign must be consistent with what God has said and done in the past, and with his character. If these tests are not passed with flying colours, we must be prepared to denounce bunkum and hokum for what they are. If we do not then we will gain a reputation for being gullible, naïve, and untrustworthy: outsiders will not have to wonder why we were so easily spooked.