Whoopi Goldberg’s argument that Hitler was obviously a Christian because he “didn’t like the Catholics” has been widely reported, but we can forgive her howler. She was speaking on The View, a fairly informal and moderately chaotic chat show which airs daily on ABC. The format does not exactly call for carefully considered analysis or erudition; and a co-host’s confused expression indicated that Goldberg’s interpretation was, at the very least, debatable.

However, mistakes about Hitler’s religious convictions are all too common and can be asserted by scholars with considerable academic pedigrees. For example, in his critically acclaimed The Better Angels of Our Nature, Stephen Pinker argues that Nazism was the product of religiosity:

… though Hitler had little use for Christianity, he was by no means an atheist, and professed that he was carrying out a divine plan. (p.677)”

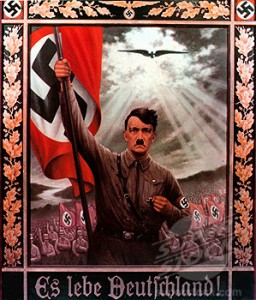

This doesn’t exactly grasp the relevant complexities. Totalitarianism was sold by the Nazis as a modern solution to modern problems. The Nazis used pseudo-religious propaganda; but they were totalitarians, and could not permit authority to exist outside the state. Therefore, traditional religions had either to be eliminated or controlled. Some Nazis preferred the latter option, adopting and manipulating the Churches as was convenient; but that is a far cry from a happy co-existence.

This doesn’t exactly grasp the relevant complexities. Totalitarianism was sold by the Nazis as a modern solution to modern problems. The Nazis used pseudo-religious propaganda; but they were totalitarians, and could not permit authority to exist outside the state. Therefore, traditional religions had either to be eliminated or controlled. Some Nazis preferred the latter option, adopting and manipulating the Churches as was convenient; but that is a far cry from a happy co-existence.

The Nazi Party did promote something which it called “Positive Christianity” in the 1920s. But from the mid-1930s onwards the Party became more and more hostile to the Church. Furthermore, “Positive Christianity” stripped Christianity of its metaphysics, essential dogmas and distinctive ethics. It was little more than a vague respect for Germany’s Protestant heritage combined with aggressive anti-Semitism. As John Conway of the University of British Columbia clarifies:

Nazi Christianity was eviscerated of all the most essential orthodox dogmas. What remained was the vaguest impression combined with anti-Jewish prejudice. Only a few radicals on the extreme wing of liberal Protestantism would recognize such a mish-mash as true Christianity.”

To understand the deep incompatibility between Christianity and Nazism, we need to reflect on the ideas which motivated Hitler. Hitler often presented himself as a German nationalist; but, as Timothy Snyder argues in Black Earth, Hitler was not a nationalist in any conventional sense. He believed that race, and the eternal struggle between the races, was more important than the nation state, which was a bloodless abstraction and not an end in itself.

Race and struggle were the central tenets of Hitler’s worldview. To his mind, nature recognised no political or moral boundaries, and our first duty was to our racial group. It was not a sin to seize riches from others and it was a crime to allow one’s competitors to survive. The only commandment he could discern was “Thou shalt preserve the species.”

Race and struggle were the central tenets of Hitler’s worldview. To his mind, nature recognised no political or moral boundaries, and our first duty was to our racial group. It was not a sin to seize riches from others and it was a crime to allow one’s competitors to survive. The only commandment he could discern was “Thou shalt preserve the species.”

It is clear that Hitler’s worldview put him at odds with the Christian faith, which Hitler came to loathe. It is true that Hitler made political deals with the Catholic Church; yet he also struck a deal with Communist Russia in 1939. Hitler was a Machiavellian politician, prepared to do a deal with whoever he wanted, whenever he wanted, so that he could betray them all at his leisure. Michael Burleigh summarises Hitler’s position neatly in his award-winning The Third Reich: A New History

National Socialism, like other totalitarian dictatorships, parodied many of the eschatological and liturgical attributes of redemptive religions, while being fundamentally antagonistic towards the Churches: rivals, as the Nazis saw it, in the subtle, totalising control of minds. However, the overwhelmingly Christian character of the German people meant that Hitler dissembled his personal views behind preachy invocations of the Almighty, and distanced himself from the radically irreligious in his own Party, even though his own views were probably more extreme.” (2001, p.717)

So Pinker’s assertion that Hitler ‘had no use for Christianity’ understates the Fuhrer’s opposition, almost to the point of dishonesty. Hitler believed that Christianity was “whole-hearted Bolshevism under a tinsel of metaphysics” and “an invention of sick brains” (Burleigh, p.718). His hostility to Christianity led to sudden radical outbursts: in early 1937 he declared that “Christianity was ripe for destruction”, and that “the Churches must yield to the primacy of the State” (Kershaw, 2008, p.382). Goebbels took notes of a speech which Hitler gave in December 1941:

So Pinker’s assertion that Hitler ‘had no use for Christianity’ understates the Fuhrer’s opposition, almost to the point of dishonesty. Hitler believed that Christianity was “whole-hearted Bolshevism under a tinsel of metaphysics” and “an invention of sick brains” (Burleigh, p.718). His hostility to Christianity led to sudden radical outbursts: in early 1937 he declared that “Christianity was ripe for destruction”, and that “the Churches must yield to the primacy of the State” (Kershaw, 2008, p.382). Goebbels took notes of a speech which Hitler gave in December 1941:

There would, he made clear, be no place in this utopia for the Christian Churches. For the time being, he ordered slow progression in the ‘Church Question’. But it is clear…that after the war it has to be generally solved…There is, namely, an insoluble opposition between the Christian and a Germanic-heroic world-view.” (Kershaw, Hitler: A Biography, 2008, p.382).

Other key figures in the National Socialist movement, like Rosenberg, Bormann, Goebbels and Himmler had a profound hatred of Christianity. Himmler, for example, considered that a belief in the sanctity of life, Christian mercy and Christian sexual morality held back the rise of the German people (Peter Longerich, Heinrich Himmler 2012, p.265). Himmler had a vague belief in a God whom he described as the Teuton “The Ancient”, a pseudo-historical reconstruction of an ancient pagan belief. Himmler rejected Christian accounts of the afterlife for belief in reincarnation (Longerich, 2012 p.269). In Longerich’s assessment:

Other key figures in the National Socialist movement, like Rosenberg, Bormann, Goebbels and Himmler had a profound hatred of Christianity. Himmler, for example, considered that a belief in the sanctity of life, Christian mercy and Christian sexual morality held back the rise of the German people (Peter Longerich, Heinrich Himmler 2012, p.265). Himmler had a vague belief in a God whom he described as the Teuton “The Ancient”, a pseudo-historical reconstruction of an ancient pagan belief. Himmler rejected Christian accounts of the afterlife for belief in reincarnation (Longerich, 2012 p.269). In Longerich’s assessment:

There is no doubt about Himmler’s anti-communism and anti-Semitism, and he sought to destroy both groups without mercy. Yet he was basically much more interested in Christianity: the conflict with the Christian world in which he had grown up had truly existential significance for him, and by linking opposition to Christians with the idea of restoring the lost Germanic world he had set himself the overriding challenge of his life….By linking de-Christianisation with re-Germanisation, Himmler had provided the SS with a goal and a purpose all of its own (2012, p.265-26)

To be fair, some historians have argued (Steigman-Gall, for example) that the relationship between the Nazis and the churches was complex. Some leading Nazis – Goering, for example – had an appreciation of Germany’s Christian past, and would have been happy to have co-exist with churches who learned to tow the party line. But did Christian theology motivate Nazis? Did Catholic or Orthodox doctrine play any part in their thinking? Those are the important questions, and the answer is a resounding “no!”