Many atheists allege that Christians use “goddidit” as a lazy approach to explaining phenomena. Every mystery is erased by invoking an all-powerful, all-knowing creator. “God-did-it” functions as a ‘science stopper’: it encourages us to abandon enquiry and research, to forsake the quest for scientific answers. However, these allegations do not withstand scrutiny.

1) Even mediaeval theologians did not accept arbitrary, miraculous actions of God as explanations for natural phenomena. They certainly believed that God was the ultimate primary cause of the physical world. However, many also believed we should not appeal to God as a primary cause unless we had direct evidence of a miracle, or could convincingly explain why God would not have brought about the same effect through secondary causes.

Mediaeval theologians were concerned to discover how God created the world through “secondary causes” – the actions of natural forces. After all, if miracles are to be spectacular events which reveal something remarkable about God, they must also be extremely rare! Furthermore, if God wrote both the book of Scripture and the book of nature, and if the two are analogous, we should be able to understand the book of nature. That is to say, nature should be comprehensible.

Mediaeval theologians were concerned to discover how God created the world through “secondary causes” – the actions of natural forces. After all, if miracles are to be spectacular events which reveal something remarkable about God, they must also be extremely rare! Furthermore, if God wrote both the book of Scripture and the book of nature, and if the two are analogous, we should be able to understand the book of nature. That is to say, nature should be comprehensible.

So, some commentators on Genesis believed that God used natural forces to part the Red Sea. Thierry of Chartres argued that “separation of the waters” above and below the heavens described in Genesis was caused naturally, as heat worked on the waters. In his reflections on the book of Genesis, William of Conches argued that life on earth arose from the natural action of heat on mud. God created the natural forces that resulted in the creation of animal and human life.

So, some commentators on Genesis believed that God used natural forces to part the Red Sea. Thierry of Chartres argued that “separation of the waters” above and below the heavens described in Genesis was caused naturally, as heat worked on the waters. In his reflections on the book of Genesis, William of Conches argued that life on earth arose from the natural action of heat on mud. God created the natural forces that resulted in the creation of animal and human life.

So “God-did-it” was not a satisfactory answer for the mind of the devout Mediaeval Christian.

2) For Kepler and Galileo “God-did-it” did not function as a “science stopper”, a phrase that explained away mysterious phenomena. Rejecting the Aristotleian focus on qualities and substantial forms, Galileo argued that the world could be understood through mathematics. Here he drew on a tradition going back to Plato, and revived by Roger Bacon (1214-192) who argued that mathematics was the “alphabet of philosophy” and the “door and key to the sciences.”

Reflect on this for a moment, placing yourself in the boots of a mediaeval philosopher: it is not at all obvious that mathematics should reveal the nature of physical things. Why should we believe that maths revealed eternal truths which are embodied in physical things?

Maths might help us make useful predictions – as astronomers and navigators had demonstrated. But that is a far cry from saying that Maths gives us a deep insight into the nature of things and how reality works. However, if the world was created by a rational agent, that agent might well have used mathematics in its design. And if we are rational agents in a world designed by a rational agent, then we might be able to comprehend that design. As Kepler wrote:

Maths might help us make useful predictions – as astronomers and navigators had demonstrated. But that is a far cry from saying that Maths gives us a deep insight into the nature of things and how reality works. However, if the world was created by a rational agent, that agent might well have used mathematics in its design. And if we are rational agents in a world designed by a rational agent, then we might be able to comprehend that design. As Kepler wrote:

“the reason why the mathematicals are the cause of natural things (a theory which Aristotle carped at in so many places) is that God the Creator had Mathematicals with him as archetypes from eternity in their simplest divine state of abstraction.”

3) So Galileo approached the world like an engineer, less interested in why objects fell than in describing how they fell, and using the language of mathematics to do so. This makes a deal more sense if the world had a designer. Physics has largely followed his example ever since.

4) Modern physics is premised on the belief that there are fundamental laws of nature which use mathematics to describe the behaviour of elementary physical substances. This notion was introduced by Christian thinkers like Rene Descartes who believed that God governed nature; he alone was responsible for the motions of the world. A belief in God’s rationality and authority and power was essential for a belief in the constancy, reliability and comprehensibility of these laws.

5) Theistic belief only predicted an ordered universe: it did not predict how God would  order the universe. A personal, free, omniscient God could choose from an immeasurable number of plans: so we cannot deduce a priori the sort of universe that God would create. Observation, measurement and experiment were necessary for a thorough understanding of creation.

order the universe. A personal, free, omniscient God could choose from an immeasurable number of plans: so we cannot deduce a priori the sort of universe that God would create. Observation, measurement and experiment were necessary for a thorough understanding of creation.

6) The fact that humans were sinful, finite creatures trying to understand the work of an infinite, perfect God gave students a further reason to test their ideas. Christianity gave us the correct balance between scepticism and faith in our human faculties.

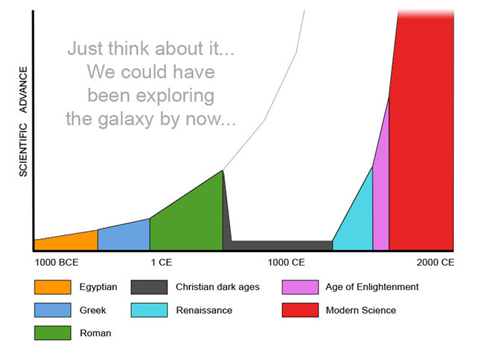

7) Unlike the Romans, Christian Europe expanded, built upon and revolutionised the resources of Greek natural philosophy. Christianity placed a value on scientific knowledge. First of all, nature revealed God’s power. So science was an aid to worship. Second, unlike Platonism, the Judaeo-Christian worldview confessed that the created world was good in its own right. This not only gave a dignity to physical crafts and labour; it meant that knowledge of the physical world was a valuable thing in its own right.

In short, Christianity only holds that God-did-it. However, it does not predict how God-did-it. So to understand how God did it, Christians nurtured the new ways of studying of the physical world: what we now call “science”!