The term “Protestant” covers a multitude of sins. Originally it referred to princes who rejected an Emperor’s right to control religious belief. Over time it came to mean anyone who rejected the Pope’s authority. So now it covers deists and fundamentalists, evangelicals and agnostics, progressives and fundamentalists, politicians and paramilitaries.

The term “Protestant” covers a multitude of sins. Originally it referred to princes who rejected an Emperor’s right to control religious belief. Over time it came to mean anyone who rejected the Pope’s authority. So now it covers deists and fundamentalists, evangelicals and agnostics, progressives and fundamentalists, politicians and paramilitaries.

For all its conservatism, Northern Ireland’s “Protestant People” is defined by a set of political attitudes to London and Dublin. It is a tribe more bound by tradition and ethnicity than any theological conviction; it is only Protestant in the sense that its members do not attend Mass. Still, the absence or presence of particular denominations in an estate or village is a visible and useful social marker. So the ‘British’ people of Northern Ireland tend to be called Protestant and the ‘Irish’ Roman Catholic.

For that reason, it is not uncontroversial to claim that “Protestant” paramilitaries killed hundreds of Roman Catholics over the last half-century. Not one murder was carried out to save a soul or to protect the three solas of the Reformation. Many unionist demagogues have not darkened the door of a church in a generation; yet they are all casually described as Protestant by the press and politicians.

For that reason, it is not uncontroversial to claim that “Protestant” paramilitaries killed hundreds of Roman Catholics over the last half-century. Not one murder was carried out to save a soul or to protect the three solas of the Reformation. Many unionist demagogues have not darkened the door of a church in a generation; yet they are all casually described as Protestant by the press and politicians.

“Islamic” has the same connotations in many parts of the West. Many Muslims do not regularly attend Mosque or practice Sharia or even keep the Five Pillars. Many have some residual loyalty to Islam, but their faith is mostly nominal. Of course it can offer spiritual comfort but it mainly functions as a social identity – just as protestantism does in Ulster. Maybe when some Western politicians criticise Islam they believe they are criticising a religious ideology. But whatever their intention, they should know that in many parts of the world their statements sound like coded racism.

“Islamic” has the same connotations in many parts of the West. Many Muslims do not regularly attend Mosque or practice Sharia or even keep the Five Pillars. Many have some residual loyalty to Islam, but their faith is mostly nominal. Of course it can offer spiritual comfort but it mainly functions as a social identity – just as protestantism does in Ulster. Maybe when some Western politicians criticise Islam they believe they are criticising a religious ideology. But whatever their intention, they should know that in many parts of the world their statements sound like coded racism.

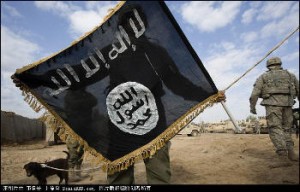

Politicians should also note that IS wishes to divide the world into the light and the dark. Those who identify with IS are, naturally, the light. Their problem is that anyone who disagrees with their vision in any way belongs to the dark – and that includes most Muslims. Unable to terrorise over a billion people spread across the globe IS hopes that the West will do their work for them. They know that every IS atrocity will be blamed on Muslims as a generic group; every mosque and madrasa will become suspect. IS will benefit as secular culture pushes Muslims further into its boundaries. The more Westerners treat Muslims as “the enemy” the stronger IS becomes.

Perhaps this is why the British government and the BBC insist on calling IS the “So-Called Islamic State”. The implication is that IS is not truly Islamic. Now, there is no doubt that the majority of the Muslim world would reject ISIS’s methods. In fact, as Jason Burke points out in The New Threat from Islamic Militancy, sympathy for terrorism has been decreasing even among conservative, reactionary Islamic communities. In fact, IS simply would not exist if Syria and Iraq had not been transformed into a lawless, stateless zone.

Perhaps this is why the British government and the BBC insist on calling IS the “So-Called Islamic State”. The implication is that IS is not truly Islamic. Now, there is no doubt that the majority of the Muslim world would reject ISIS’s methods. In fact, as Jason Burke points out in The New Threat from Islamic Militancy, sympathy for terrorism has been decreasing even among conservative, reactionary Islamic communities. In fact, IS simply would not exist if Syria and Iraq had not been transformed into a lawless, stateless zone.

Elsewhere we have argued that Muhammad, Abu Bakr, Umar and the other leaders of the first Islamic communities would have rejected ISIS’s methodology. Whatever else they were, these men and women were shrewd politicians who would realise that IS’s attempt to build a superpower through propaganda and terrorism is not merely impractical – it is ludicrous. IS might threaten Western, Russian and Iranian interests – but it does not pose an existential threat to any major power.

Still, we have also argued that Islam is essentially diverse. Of course, there are some key beliefs which unite all Muslims: a strong commitment to monotheism, a belief that Muhammad is God’s final messenger, and that the Koran is the supreme revelation from God. Now, a liberal reformist, a Sufi Pir, and an Islamist radical will interpret the Koran in very different ways. And Islam simply does not prescribe one form of government or one form of political engagement. Islamic communities evolve and change; they can continually renegotiate their relationship with the state.

Still, we have also argued that Islam is essentially diverse. Of course, there are some key beliefs which unite all Muslims: a strong commitment to monotheism, a belief that Muhammad is God’s final messenger, and that the Koran is the supreme revelation from God. Now, a liberal reformist, a Sufi Pir, and an Islamist radical will interpret the Koran in very different ways. And Islam simply does not prescribe one form of government or one form of political engagement. Islamic communities evolve and change; they can continually renegotiate their relationship with the state.

Still, IS is committed to monotheism, Muhammad’s authority and the supremacy of the Koran. It follows that it is in some sense Islamic. To be clear, it does not resemble the Islam practised by most Muslims, it does not reveal the true nature of Islam (whatever that means) and it will not survive for long. Eventually the diversity of Islam will undermine IS; Muslims will not consent be governed by one, monolithic vision of their religion.

But if it is reasonable to refer to protestant paramilitaries, or to write histories of the Christian crusader, or to note that Christian paramilitaries massacred Muslims at Sabra and Shatila, then it is reasonable to refer to IS as the Islamic State. The British establishment should simply stop talking about Islam (or any religion) as a monolithic group which can be comprehended in a sound-bite. It should not have to explain that there are numerous conflicting interpretations of Islam. We already know this.

What we need to hear are Muslim criticisms of IS and violent jihadism. These are not in short supply. In fact, if our own experience can be a guide, referring to IS as the Islamic State it might be helpful in another way. Whenever Northern Irish evangelicals heard about “protestant” paramilitary atrocities we were forced to ask if we were in any way complicit in these crimes. Had we said or done anything to encourage or even rationalise such behaviour? We had to explain how our values differed from those who defended their politics with hatred and murder.

Whenever evangelicals are confronted with the Crusades, or the Inquisition, or the Witch Trials, or the Thirty Years War we are forced to confront history. We must explain why these events do not follow from Christian theology or ethics. This, in turn, forces us to think about violence and conflict and what we can do to promote tolerance. Criticism breed the need for religious; religious apologetics gradually teaches the value of civility. Perhaps those who wish to promote civility will, in turn, recognise the value of religious apologetics and give Muslim critics of IS a greater voice.

Whatever the arguments for and against, the name IS is here to stay and there is no strong argument against using it. It is true that words and images matter to IS; but to the rest of humanity arguments matter a great deal more. We do not need to agonise over what to call IS: instead we need to hear their world-view argued out of existence.

See also: Would Muhammad Join ISIS?