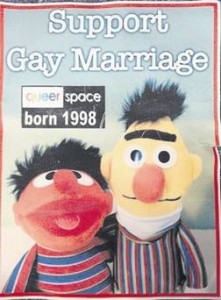

Few would have thought that it would cost £88500, freedom of conscience and essential religious liberties to make a simple iced cake. Yet that may be what the Equality Commission has just charged. In 2014, Christian bakers at Ashers Baking Company declined to make a cake for Gareth Lee because the cake was to carry the message “Support Gay Marriage”. Lee, a gay rights activist, believed that he had been discriminated against and, with financial backing from Northern Ireland’s Equality Commission, took the bakers to court.

Later in the year District Judge Isobel Brownlie ruled the directors of Ashers had unlawfully discriminated against Mr. Lee; this week an Appeal court concurred that Ashers had indeed acted unlawfully. The court accepted that Asher’s would not have served a straight man who ordered a cake which said “support gay marriage” and that it would have served a homosexual man if he had ordered a cake with the message “support traditional marriage” .

Later in the year District Judge Isobel Brownlie ruled the directors of Ashers had unlawfully discriminated against Mr. Lee; this week an Appeal court concurred that Ashers had indeed acted unlawfully. The court accepted that Asher’s would not have served a straight man who ordered a cake which said “support gay marriage” and that it would have served a homosexual man if he had ordered a cake with the message “support traditional marriage” .

However, the court did not accept that this was a sufficient answer to the discrimination claim. For very good reason, a person need not have a protected characterstic to be discriminated against; it is unlawful to discriminate against someone “because of” a protected characteristic. So, a company would be unlawfully discriminating against Roman Catholics by refusing to employ protestants married to Roman Catholics, even though those protestants do not possess the protected characteristic.

In the Court’s view, Ashers was guilty of discrimination because of sexual orientation because the message on the cake was inextricably linked to having a particular sexual orientation. This suggests one problem with the ruling: the law was designed to protect persons, not slogans. Furthermore, the ruling tramps over ground which many Christians and secularists consider sacred: it undermines the sanctity of the individual’s conscience.

The court was at pains to point out that it was not singling Christians for harsh treatment:

If the Plaintiff was a gay man who ran a bakery business and the Defendants as Christians wanted him to bake a cake with the words ‘support heterosexual marriage’ the Plaintiff would be required to do so as, otherwise; he would, according to the law be discriminating against the Defendants. This is not a law which is for one belief only but is equal to and for all.

At least this makes plain that it is not merely religious, but also secular convictions, which could suffer under current equality legislation. But surely it is horrific to expect a homosexual to promote and profit from a message he considers homophobic. And it seems particularly unjust – and somewhat ludicrous -to expect anyone to produce material which conflicts with their conscience when that material can easily be purchased elsewhere.

The court argued that Ashers conscience should not have been disturbed because it was not endorsing a message by printing it; the judge offered the following analogy:

…the fact that a baker provides a cake for a particular team or portrays witches on a Halloween cake does not indicate any support for either.

But this misses the point by some distance. A better analogy would have a baker producing a cake which celebrates a divorce or which promotes a Wiccan festival; most evangelicals would find it impossible to create either. If a message deeply conflicts with a person’s core beliefs and identity then it is unwise and inhuman to expect that person to amplify or reproduce them.

On the BBC web-site Joshua Rozenberg argued that this ruling will not adversely affect religious communities:

There are plenty of shops and restaurants in Great Britain that sell only kosher or halal food but their religiously-observant owners will normally serve any customer who comes through the door. That, after all, is what the law requires.

But, again, this misses the point. A Palestinian printer could be asked to produce leaflets which defend the Israeli policy on the West bank; a Muslim baker could be asked to write “God is not great” on a cake. Dr Michael Wardlow, director of the Equality Commission, believes that he can cut such Gordian knots with several neat strokes. Religious business owners should simply make financial sacrifices and restrict the good and services they offer. And, if that fails, they should consider that”maybe that is not the business they should be in.”

So freedom of conscience is the freedom to go bankrupt and to be unemployed. That is far from reassuring. There is a clear need for nuanced and robust legislation to protect our ability to live in accordance with our deepest beliefs. No one is suggesting that the law be made subject to the whims and pangs of the individual’s scruples. Rather, the law should protect what we could call “soul freedom”.

So freedom of conscience is the freedom to go bankrupt and to be unemployed. That is far from reassuring. There is a clear need for nuanced and robust legislation to protect our ability to live in accordance with our deepest beliefs. No one is suggesting that the law be made subject to the whims and pangs of the individual’s scruples. Rather, the law should protect what we could call “soul freedom”.

A citizen should only be made exempt from legislation when that legislation dictates that he or she must act against a central aspect of their faith or world-view. To be exempted, a claimant would need to demonstrate that legislation substantially burdens a sincerely held belief; they would also need to show that this belief plays an important role in guiding their community or tradition. Furthermore, legislation should only be used to compel citizens to go against their consciences when it can be established that there is a clear, compelling need to do so.

This would not open the door to anarchy. The law need not tolerate behaviour which is wilfully absurd or which restricts the freedom of others; furthermore, the government would have a compelling interest to intervene if any subsection of society faced widespread discrimination. But there is no compelling state interest in forcing religious citizens to provide goods and services which promote or condone beliefs they strongly disagree with when those goods or services can be found easily elsewhere.

Mr Lee – who seems like decent, conscientious man- sought recompense from Ashers because their refusal made him feel like a lesser person. But now those with deep convictions must consider if there is any room for them in the market-place and the public square. They may now wonder if society now regards them as lesser persons. Principled pluralism cannot survive in such conditions. If civil society is to thrive, we need better laws, and soon.

When @TheTelegraph__ and @guardian are both questioning the judgment in the #gaycake case, you realise it’s far from clear-cut. #Ashers

— David Blevins (@skydavidblevins) October 25, 2016