Culture warriors might be interested in events North of the Irish border, as the Presbyterian Church in Ireland has decided that:

same-sex couples are not eligible for communicant membership nor are they qualified to receive baptism for their children.

This decision has caused some controversy within the Presbyterian church; but the reaction in the secular press has tended towards the hysterical. Perhaps this is not surprising; at the same time the Republic of Ireland has conservatives on the run, the North’s largest Protestant denomination has reminded us that the North is not yet secular.

This decision has caused some controversy within the Presbyterian church; but the reaction in the secular press has tended towards the hysterical. Perhaps this is not surprising; at the same time the Republic of Ireland has conservatives on the run, the North’s largest Protestant denomination has reminded us that the North is not yet secular.

Consider the coverage by The Belfast Telegraph , which consistently describes the current controversy as an apocalyptic conflict for the very survival of the church, fought between “fundamentalists” and “moderates”. Of course, a battle between black-hatted, benighted reactionaries and enlightened white-hatted reformers make for an entertaining press narrative. But the analysis is, quite frankly, irresponsible and misleading.[1]

The paper really ought to take some advice from the The Associated Press Stylebook, which warns, “in general, do not use ‘fundamentalist’ unless a group applies that term to itself.” For, as the Stylebook quite reasonably notes, the term ‘fundamentalist’ has taken on “pejorative connotations” in recent years. We commonly (and unhelpfully) refer to Islamic terrorists as fundamentalists, for example.

And, in a justifiably famous passage, the Western world’s premier philosopher of religion, Alvin Plantinga, noted that “fundamentalism” is a term with emotive force, but little content:

…. In the mouths of certain liberal theologians, for example, it tends to denote any who accept traditional Christianity, including Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, and Barth…. its cognitive content is given by the phrase ‘considerably to the right, theologically speaking, of me and my enlightened friends.’ The full meaning of the term, therefore (in this use) can be given by something like ‘stupid sumbitch whose theological opinions are considerably to the right of mine.’.”

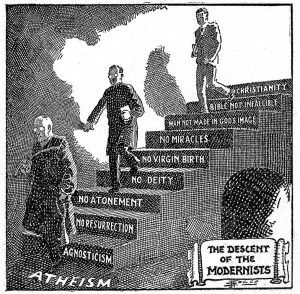

In fact, it is not very difficult to define and detect Protestant Fundamentalism. Anglo-American Protestant Fundamentalism arose in the late 1800s and developed significantly between the two world wars. It refers to groups who refuse to have fellowship with Roman Catholics, Liberals and Ecumenicals; and who also withdraw from conservative Protestants who do have fellowship with those groups.

Additionally, Fundamentalists do not settle for the doctrines of biblical inerrancy or infallibility, but further insist on a strict, literalist interpretation of scripture. If the plain sense of a verse makes good sense then no other sense is sought. As an example, Fundamentalists insist that a faithful Christian must interpret the Creation accounts literally. They have little or no patience for theologians who see poetic or other non-literal elements in Genesis 1-3.

Additionally, Fundamentalists do not settle for the doctrines of biblical inerrancy or infallibility, but further insist on a strict, literalist interpretation of scripture. If the plain sense of a verse makes good sense then no other sense is sought. As an example, Fundamentalists insist that a faithful Christian must interpret the Creation accounts literally. They have little or no patience for theologians who see poetic or other non-literal elements in Genesis 1-3.

There are other distinguishing features: a hostility to secular education, a suspicion of Church hierarchies and a rejection of tradition. Suffice to say, I do not know of any Presbyterian elder or minister who is a Fundamentalist. I know many Fundamentalists[2], but none are in the Presbyterian clergy. But I do know of Presbyterian ministers who are Evangelical; and none are Fundamentalists.

As with Fundamentalism, so with Evangelicalism: it is not so difficult to define and detect. An Evangelical is an orthodox Protestant [3] who stands in the tradition of the movements associated with John Wesley and George Whitefield; who believes the Bible is vital, accurate, accessible and authoritative; who believes we all must be personally reconciled to God through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross; who stresses the work of the Holy Spirit in making our faith living and active; and who believes all Christians have a duty to spread the Gospel to others.

Evangelicals do not feel compelled to interpret every text literally; they are not as insular as fundamentalists; and many are prepared to remain in denominations with clergy who do not share their theology. Fundamentalists dismiss Evangelicals as closet Liberals and Liberals dismiss Evangelicals as closet Fundamentalists. But, while such dismissals have rhetorical force, they have no rational force.

However, Evangelicals do tend to view the Christian life as a demanding affair; as we have noted, they stress the role of the Holy Spirit in making faith living and active. Furthermore, the Son of God’s sacrifice requires a response:a deep, existential commitment to Christ. Although Christians can do nothing at all to earn their salvation, such a commitment brings about a change in behaviour and character.

However, Evangelicals do tend to view the Christian life as a demanding affair; as we have noted, they stress the role of the Holy Spirit in making faith living and active. Furthermore, the Son of God’s sacrifice requires a response:a deep, existential commitment to Christ. Although Christians can do nothing at all to earn their salvation, such a commitment brings about a change in behaviour and character.

Naturally, such change has a cost; and this cost is not evenly spread among believers. Some will be violently persecuted; some will face systematic discrimination and social exclusion; neither is true of believers in Northern Ireland. However, many careers, friendships and romantic partnerships will not survive a person’s conversion to Christ. Some seemingly minor lifestyle choices, considered quite harmless and insignificant by secular society, will have to be rejected. It is not at all unusual for Evangelical Christians to be quietly mocked or subtly stigmatised as a result.

I suspect that it is the Evangelical view of the Christian life which influenced the Presbyterian Church to exclude people in same-sex partnerships from full membership. Evangelicals tend to view deep Christian commitment as a prerequisite for Church membership; their commitment to the authority of scripture leads them to very conservative beliefs about sexual morality. In this context, the Presbyterian churches’ position is not surprising at all. And without a clear, striking argument against Christian orthodoxy, it is not at all irrational.

All this will require some explaining to an uncomprehending and unsympathetic public. The Christian gospel is already offensive enough; unnecessary hurt is added to unintentional insult when Evangelicals speak without clarity. Evangelical attitudes can then seem callous and intolerant. My bet is that Evangelicals need to articulate their vision for the church and its place in society; and they need to do this is terms that a secular culture will understand.

The Belfast Telegraph worries that the rise of conservative theology will lead to the death of the church. There is no doubt that it would lead to a decrease in nominal Christianity and latitudinarian attitudes among church leaders. But that will only be good for the church. A lifeless faith is dead and useless; and, as it happens, evangelical churches seem to survive as mainline churches dwindle in numbers and die.

Mainline denominationalism will probably continue to decline in significance and popularity; evangelical churches might well become dominant. It is important, then, for secular journalists to learn more about evangelicalism; but evangelical Christians cannot expect sympathy if they will not speak with a clearer voice.