Conservative MPs – Sir Gerald Howarth, David Burrowes, Gary Streeter and Fiona Bruce MP- have criticised government proposals to send inspectors into Sunday Schools, church youth groups, Scout troops and Boy’s Brigades to search for signs of radicalisation. The government is worried that a number of madrassas are preaching “hatred” and it would like to crack down on the anti-western, anti-semitic world view taught in some of those establishments. It is also keen to promote “British values” to provide an alternative to Islamo-facism and unite citizens in opposition to it.

Conservative MPs – Sir Gerald Howarth, David Burrowes, Gary Streeter and Fiona Bruce MP- have criticised government proposals to send inspectors into Sunday Schools, church youth groups, Scout troops and Boy’s Brigades to search for signs of radicalisation. The government is worried that a number of madrassas are preaching “hatred” and it would like to crack down on the anti-western, anti-semitic world view taught in some of those establishments. It is also keen to promote “British values” to provide an alternative to Islamo-facism and unite citizens in opposition to it.

Of course, it would be unfair to serve sauce with the goose and not the gander. So the ministers would like to send inspectors to Christian organisations as well. So the four MPs expressed their concerns in a letter to the Daily Telegraph

Yesterday saw the end of a Government consultation on proposals for out-of-school groups to register and be subject to Ofsted inspections in order to ensure they comply with British values.

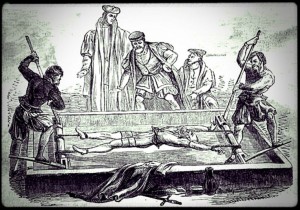

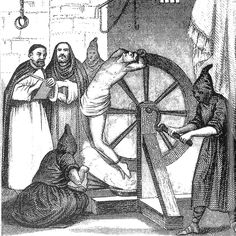

If implemented, these regulations could have a seriously detrimental effect on the freedom of religious organisations. These groups fear the prospect of an Ofsted inspector observing meetings and then imposing sanctions for the expression of traditional views on matters such as marriage – views which, until very recently, were considered mainstream in Britain.

This would be an intolerable but very real possibility given the clear desire of the Department for Education to investigate what it calls “prohibitive activities”, such as “undesirable teaching… which undermines or is incompatible with fundamental British values”. This could challenge established Christian teaching.

Their worries do not seem misplaced or overstated. It seems that the secular state would like to regulate religion in the name of security. This is both a severe encroachment on our liberty and completely unnecessary. The government already has a remarkable tool for deconstructing radicalism in every state-funded school – the Religious Education department.

Their worries do not seem misplaced or overstated. It seems that the secular state would like to regulate religion in the name of security. This is both a severe encroachment on our liberty and completely unnecessary. The government already has a remarkable tool for deconstructing radicalism in every state-funded school – the Religious Education department.

Religious Studies is underfunded and undervalued, but it could play a vital part in restoring some sense of British identity, some faith in British values and in challenging extremism. Consider the values the government wishes to defend and promote. “Individual liberty”, “tolerance”, or “respect for democracy and the rule of law” are all well and good, but they hardly form a rigorous, compelling moral world-view. Nor do they even define anything distinctively British. We cannot establish a future without building on our past; and to build on the best of our past we must have some understanding of Christianity.

Every country which has been populated by human beings has something to be ashamed of: in our case the slave trade, racism, colonialism, imperialism and religious discrimination. But there is more to our history than depravity and rot; good foundations can be found in the stories of Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights, Olouba Equiano, Catherine Booth, the Royal Society, Wilberforce, Shaftesbury, Florence Nightingale and Emily Davison. Any historical narrative of the British peoples must take account of their relationship with Christianity. Every Briton should appreciate the “Free-Thinking” tradition which includes luminaries from Tindal and Collins, through Hume, Shelley and Russell. But how can anyone understand them without comprehending the world-view they rejected?

We live in a state of denial; too many politicians, journalists, screenwriters and educators treat orthodox Christian belief either as an object of scorn, or as something that polite, educated people do not mention in public. This insouciant ignorance about religion in general, and Christian doctrine in particular, creates a vacuum in our self-understanding.

We live in a state of denial; too many politicians, journalists, screenwriters and educators treat orthodox Christian belief either as an object of scorn, or as something that polite, educated people do not mention in public. This insouciant ignorance about religion in general, and Christian doctrine in particular, creates a vacuum in our self-understanding.

What is required is a retrieval of our relationship with Christianity; and Religious Education should play an important role in the recovery. This is not to endorse catechisation in our classrooms. Obviously, students can disagree with the Christian world-view; but every pupil should be aware of it, know the various ways it has manifested itself in British history, and understand how it has shaped our intellectual and moral environment. They should also be able to articulate and evaluate alternative worldviews and secularist criticisms of religion in general.

In fact, some exam boards have excellent models which could be developed into such a programme. CCEA provides an excellent structure for studying Christianity; AQA’s schemes for GCSE enable a class to examine Christianity critically, comparing aspects of Christian thought to at least one other religion and a secular alternative. The approach taken by AQA actively encourages critical thinking, civil debate and rational disagreement (top marks are not awarded unless pupils can argue for and against a proposition). By insisting on a study of several religions, students avoid a narrow minded parochialism and an appreciation of other world-views.

Of course, the academic study of Islam will help students not only reject, but argue against propagandists. Jason Burke points out that the majority of “lone-wolves”, who travel great distances at great risk and some expense to train as terrorists, were once disengaged, marginalised petty-criminals. They begin with little interest in, and less knowledge of, Islam. So, when they encounter an Islamic community which gives them a sense of belonging and purpose, they cannot critically assess their claims. If that community preaches a violent jihado-centric interpretation of Islam they will accept it as a given. So it is essential to acquaint students with the essential diversity of the Islamic world and the debates that have emerged within it.

Students should also be made aware of the intellectual depth of the Islamic intellectual tradition and Europe’s debt to Muslim scholarship. The Mutazilites deserve a special mention – mediaeval philosophers, scientists and politicians who stressed the importance of reason, humane values and who denounced strict, Shariah based faith. That is to say, there are powerful Muslim critiques of extremism which students need to be aware of. The government simply would not need to censor Deobandi or Wahabi madrassas if it used schools to critically assess extremist claims and to interest students in alternatives.

Students should also be made aware of the intellectual depth of the Islamic intellectual tradition and Europe’s debt to Muslim scholarship. The Mutazilites deserve a special mention – mediaeval philosophers, scientists and politicians who stressed the importance of reason, humane values and who denounced strict, Shariah based faith. That is to say, there are powerful Muslim critiques of extremism which students need to be aware of. The government simply would not need to censor Deobandi or Wahabi madrassas if it used schools to critically assess extremist claims and to interest students in alternatives.

We should not teach religion to produce specific political, philosophical or religious beliefs in our pupils. Parents must not feel that a school is arrogantly and callously undermining their values. Adolescents dislike sermons and would argue that day is night if given the opportunity. We need merely address the big questions of philosophy, religion and ethics from these different perspectives and help the young people clarify and defend their own beliefs. Teenagers are not vapid blank slates who uncritically absorb every idea the education system throws at them. In fact, given the chance, most are capable of a nuance and sophistication which would embarrass older generations (and some politicians).

Through knowledge, debate and discussion, students will develop a range of valid responses to the ideas and movements that have shaped our country and form a variety interpretations of what it means to be British. Of course, this will mean more investment in schools and teacher training; trendy subjects like citizenship may have to give way to the academic study of religion. But his is a smaller price to pay than giving up a chunk of our religious freedom. So a little faith in our students will accomplish so much more than an inspector calling at the Sunday School door.