This site has argued that Christians should have freedom of conscience to choose between political candidates and parties. Not that any evangelical church has the power to prevent someone voting how they like – but subtle pressures are often brought to bear in sermons and articles. For example, an article by Rick Phillips on Reformation 21 has strongly suggested that a vote for Bernie Sanders (and presumably Jeremy Corbyn) is a vote for evil. This is not because either man is pro-choice; it is because they are both socialists.

Now, Sanders is no Marxist, so I can only suppose that Mr Phillips is opposed to the politics of the left. To some extent I sympathise; the left has capitulated to secularism. I also agree that it is wrong for Christians to “denounce capitalism and laud socialism” as the more biblical alternative. Neither term would have been comprehensible to the biblical writers and neither concept would have made the least bit of sense to them. Either system can become an ideology and all ideologies can become idols. But as long as political parties and platforms are treated with a good dose of biblical scepticism Christians should have liberty to decide which system best serves the poor and establishes justice.

Now, Sanders is no Marxist, so I can only suppose that Mr Phillips is opposed to the politics of the left. To some extent I sympathise; the left has capitulated to secularism. I also agree that it is wrong for Christians to “denounce capitalism and laud socialism” as the more biblical alternative. Neither term would have been comprehensible to the biblical writers and neither concept would have made the least bit of sense to them. Either system can become an ideology and all ideologies can become idols. But as long as political parties and platforms are treated with a good dose of biblical scepticism Christians should have liberty to decide which system best serves the poor and establishes justice.

Mr Phillips would, presumably, disagree, for he argues that

Christians should also have enough discernment not to endorse a system so inherently evil as socialism. So, biblically speaking, why is socialism evil? Let me suggest three reasons: 1. Because socialism is a system based on stealing; 2. Because socialism is an anti-work system; and 3. Because socialism concentrates the power to do evil.

There are a few problems here, all of which I would cheerfully ignore if Mr Phillips had not trod on a note of apologetic concern. In the United Kingdom many evangelicals, particularly Methodists, were major contributors to the labour movement. This grew naturally out of their constituency and their theology of work. But if evangelicals were instrumental in founding a movement which led to a left-wing, working class, “socialist” political party then, on Mr Phillips logic, evangelicals have made the world more Satanic.

There are a few problems here, all of which I would cheerfully ignore if Mr Phillips had not trod on a note of apologetic concern. In the United Kingdom many evangelicals, particularly Methodists, were major contributors to the labour movement. This grew naturally out of their constituency and their theology of work. But if evangelicals were instrumental in founding a movement which led to a left-wing, working class, “socialist” political party then, on Mr Phillips logic, evangelicals have made the world more Satanic.

Mr Phillips believes that “socialism” is quasi-totalitarian, pro-theft and anti-work. But in point of historical fact, England’s labour movement was instrumental in dignifying work, preventing violent revolution and in ensuring a fairer deal for the industrial working classes. It is generally acknowledged that Methodism in general, and the Primitive Methodists in particular, laid the intellectual and organisational foundation for the labour movement in the early nineteenth century. Indeed, the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawn wrote that ‘ … it is not too much to think of them as primarily a sect of trade union cadres.’

Methodism was in itself a form of protest – merely opening a Methodist Chapel defied the local Anglican Church, challenging the power of the propertied classes. These new chapels did not merely preach that every person had equal access to God and that every believer was a priest in a holy nation. They insisted on educating workers because every Christian should be able to read and contemplate the scriptures.

Methodism was in itself a form of protest – merely opening a Methodist Chapel defied the local Anglican Church, challenging the power of the propertied classes. These new chapels did not merely preach that every person had equal access to God and that every believer was a priest in a holy nation. They insisted on educating workers because every Christian should be able to read and contemplate the scriptures.

There was little room for paternalism in these new congregations. Often lacking enough ministers to serve all the churches in a circuit, labourers were taught to read, write and to preach in public. Wesley’s own concern for social justice filtered its way down to the laity. Although the clergy generally insisted that churches stay out of political movements, many Methodist lay preachers began to call for a social equality in line with their denomination’s demand for spiritual equality.

Many leader of the new labour movement were converted by Methodist preaching and went on to work as lay preachers. For these evangelicals the fact that God was no respecter of persons seemed to have radical and progressive implications. They seem to have had a point: capitalists and aristocrats benefited disproportionately from the nation’s laws and resources.

One Methodist preacher repeatedly complained that the mills were made from ‘gold coined out of the blood and bones of the operatives’. One wonders what he would have made of Mr Phillip’s allegation that socialism is a form of theft.[i] Workers were not only robbed of their fair share of the mill’s profits. In many cases they were also robbed of their health, their lives, and even the lives of their children.

But doesn’t socialism undermine our desire to work by offering free education, free health care, and free vacation time? Not at all. This may come as a surprise, but the labour movement has always insisted on the dignity of labour. The industrial revolution may well have been impossible without this message. When it began agricultural labourers could produce enough food by working for two thirds of the year, with 80 full days and 70 part days free from work. The first industrialists had to encourage such workers to leave this lifestyle behind for fewer holidays and longer hours.

True, living conditions would improve significantly between 1750 and 1850; but the first families to toil in the mills could not have known this. Why did poor people labour at monotonous tasks in dismal conditions? As Charles Edward White explains in his paper “Charles Wesley and the Making of the English Working Class” workers could induced to work long hours for more than 300 days a year because “they sang the hymns of Charles Wesley”. These hymns taught 19 important lessons, all grounded in scripture:

1. God calls believers to work—even to boring work. 2. Such work can be done in the Lord’s name and with a good attitude. 3. Such work advances God’s glory. 4. Such work is a holy sacrifice. 5. God himself will accept it as an offering. 6. Christians should follow the leadership of their bosses, even unworthy ones. 7. Christ enables believers to bear the hardships of the workplace. 8. Jesus himself assigns the particular task to each laborer. 9. Successful performance of work brings glory to God the Father and to Jesus, God the Son. 10. Daily labor is a means God uses to sanctify believers. 11. Jesus accompanies them in their work. 12. Any work is noble. 13. God evaluates work, and even judges the motives with which it is done. 14. Work is part of Jesus’ easy yoke. 15. Work hastens the coming of the Lord. 16. Work comes to us not as a curse, but as part of God’s bounteous grace. 17. Work is a delight that brings Christians joy. 18. Work bring believers closer to heaven. 19. Work allows people to experience heaven on earth.

But wasn’t this just opium for the people? A system of religious terrorism which kept the poor joyless and penniless while the rich ruthlessly exploited their piety? Hardly.

Not only were there more people with a better standard of living, but also it was during the Industrial Revolution that workers, transformed by Wesley’s theology of work, “began to exercise effective and sustained control over their own lives, and to have sustained political and industrial power, for the first time in history.” Thus England and Wales, while empowering their workers, were also producing approximately three times as much food and other necessities as they had a century before.

Now, to be clear: only a fool would say that the labour movement was more “evangelical” or “biblical” than conservatism. Lord Shaftesbury was a man of conservative convictions who did more to help the working poor than many a socialist. So Christians should not hitch their wagon to a particular political party. “Liberty of conscience” is an important Christian doctrine: individual Christians have the right to form their own opinions about a wide variety of policies and programmes.

Now, to be clear: only a fool would say that the labour movement was more “evangelical” or “biblical” than conservatism. Lord Shaftesbury was a man of conservative convictions who did more to help the working poor than many a socialist. So Christians should not hitch their wagon to a particular political party. “Liberty of conscience” is an important Christian doctrine: individual Christians have the right to form their own opinions about a wide variety of policies and programmes.

The Bible is clear that we should respect creation – but it does not tell us how to interpret the data about global warming. The Bible tells us to protect the poor, respect property and obey the government – but it does not make suggestions for ideal tax-free personal allowances. By creating room for debate, Christians are better placed to find more efficient means for the ends we all share. Above all, we must not give the impression that Christianity is primarily about moralism, social conservatism or even the redistribution of wealth (and, to be fair, Mr Phillips would agree with us wholeheartedly).

We need to be clear: Christians do not evangelise so that citizens will vote in a socially conservative manner; we do not preach so that people will assent to the Christian world-view. The Sadducees were social conservatives and the devil’s metaphysics are probably quite sound. Instead, we preach faith in Christ and a labour that comes from love. Only a hope stored up in heaven insures against cynicism now on Earth.

[i] Perhaps Mr Phillips would argue that he was not arguing against fair wages and working conditions, but against institutions like Britain’s much maligned “Welfare State”. But this overlooks the debate which led to the creation of the welfare state.

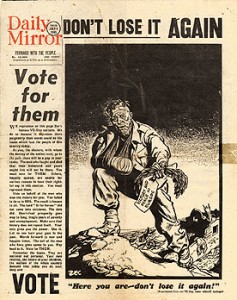

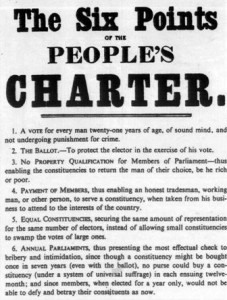

In the 1945 election which swept the much loved Churchill out of power, and the Labour Party into power, “socialists” argued the undeniable point that it was the workers who had suffered most to protect Great Britain. Therefore, it would be an act of theft to allow plutocrats and aristocrats to profit from their toil. Britain’s workers had earned a right to a fairer deal in housing, health and wages.

The rich should not be allowed to steal the greater proportion of the Britain’s wealth for themselves if the labour of the workers had produced it. Some redistribution of the nation’s resources seemed justified to the electorate. Now, this argument could be debated, back and forth, and for some time. But that is just the point. It must be debated: and in a fallen world of mixed motives and scarce resources, neither side can settle the matter by shouting “thief” at the other.