So the church believes that marriage is part of God’s plan for us; that monogamy as written into God’s creation (see part 1). But hold on: isn’t everyone awash with passions which conflict with this view of human nature? True, on one level we’d all like to fall deeply, passionately in love with one person for the rest of our lives. But, in practice, people fall in and out of love all the time, and relationships wax and wane. Most would admit to at least some desire for multiple sexual partners; in fact a multi-billion dollar industry can generate huge profits from the male desire for sex with young, attractive females. This is hardly evidence that we’re hardwired for monogamy!

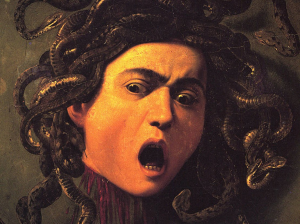

Two points can be made in reply. First of all, some plans are difficult to follow; they call for deep commitment, even life-long sacrifice. That hardly makes them dispensable or irrational. Second, Christians explain that we all have fallen natures. A musician’s instrument might have been exquisitely formed and finely tuned; but it will play a terrible tune if it is neglected and misused. And Christians insist that humans have been misusing human nature for millennia. After all, we were designed to walk in fellowship with God; at some point in the past, we opted out of that relationship. We are left with damaged, crooked souls, twisted out of shape.

This is quite a convincing portrait of human nature. After all, we all experience irrational anxieties and frivolous ambitions; we nurse our grievances and begrudge our neighbour’s successes. We are given to inordinate fury when we are wronged; yet we demand that our friends be paragons of patience. We want the universe to revolve around our appetites, so we persistently seek to put these ahead of the needs of others.

Our emotions are, more often than not, selfish, disordered, irrational and undesirable. They are “contrary to nature”; they do not fit with God’s design for us. Yet somehow we know that much of what we feel and want is wrong; we know that we ought to strive to be better. It is almost as if we are aware of a deeper, better plan than the course of action dictated by our desires. It is almost as if there is a law written on our hearts which, when we listen, overrules our worst feelings.

Our emotions are, more often than not, selfish, disordered, irrational and undesirable. They are “contrary to nature”; they do not fit with God’s design for us. Yet somehow we know that much of what we feel and want is wrong; we know that we ought to strive to be better. It is almost as if we are aware of a deeper, better plan than the course of action dictated by our desires. It is almost as if there is a law written on our hearts which, when we listen, overrules our worst feelings.

Now, we never asked to be “born this way”; but we should admit that we enjoy the experiences provided by lust, pride, wrath, sloth and greed. Sometimes we approve of what they make possible; vice often leads to quick results, after all. If it wasn’t for lust, we could not have the thrill of affairs. If it wasn’t for avarice, we couldn’t enjoy luxury. In other words, we connive with our twisted natures, and when we do so we are culpable.

We know we are not what we ought to be – but most of the time, we’re not that bothered. A hundred times a day we enjoy feeling superior to our fellow humans, or indulging our desires more than is healthy or wise, or being needlessly hurtful to the people who share our world. But it seems to be beyond our power to fix these faults, to untwist the crooked timber in our souls? So how could anyone find fault with us?

Because we don’t fight as hard as we could and should. But, above all, want and seek and find outside help; and we don’t. We need someone outside creation to provide hope, a better future; someone who can forgive, transform and heal our natures. In short, we need grace. By focusing on nature, on what we should be and how we fall short, we are pointed to the gospel. And the gospel is the whole point of the church. It is not something that Presbyterians – or any other – denomination can retreat from.

Because we don’t fight as hard as we could and should. But, above all, want and seek and find outside help; and we don’t. We need someone outside creation to provide hope, a better future; someone who can forgive, transform and heal our natures. In short, we need grace. By focusing on nature, on what we should be and how we fall short, we are pointed to the gospel. And the gospel is the whole point of the church. It is not something that Presbyterians – or any other – denomination can retreat from.

And that is why the Presbyterian church said that some relationships are “against nature”; and that is why they are being so cussedly stubborn about their sexual ethics. While I might wish they had explained themselves better, there is more at stake than the public’s perception of the church or hurt feelings. The churches view of nature and grace – that is to say the churches message and worldview – are at stake.